Marxism is the political philosophy and practice derived from the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism holds at its core a critical analysis of capitalism and a theory of social change. The powerful and innovative methods of analysis introduced by Marx have been very influential in a broad range of disciplines. In the 21st century, we find a theoretical presence of Marxist approaches in the western academic fields of anthropology,[1][2] media studies,[3] theater, history, Sociological theory, education, economics,[4] literary criticism, aesthetics, and philosophy.[5]

馬克思主義是馬克思(Karl Heinrich Marx)、恩格斯(Friedrich Engels)在19世紀工人運動實踐基礎上而創立的理論體系。馬克思主義主要以唯物主義角度所編寫而成。

馬克思主義理論體系包括三部分,即馬克思主義哲學、馬克思主義政治經濟學、科學社會主義,分別是馬克思、恩格斯受德國古典哲學、英國古典政治經濟學、法國空想社會主義影響,並在此基礎上創立的。

目錄

1 內容

2 影響

3 著作

4 參考

5 外部連接

(Cited from: http://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E9%A6%AC%E5%85%8B%E6%80%9D%E7%A4%BE%E6%9C%83%E4%B8%BB%E7%BE%A9&variant=zh-tw)

2. L.S. Vygotsky 1925

“Consciousness as a problem in thepsychology of behavior”

http://www.marxists.org/archive/vygotsky/works/1925/consciousness.htm

3. George Herbert Mead

George Herbert Mead (February 27, 1863 – April 26, 1931) was an American philosopher, sociologist and psychologist, primarily affiliated with the University of Chicago, where he was one of several distinguished pragmatists. He is regarded as one of the founders of social psychology.

Contents

1 Biography

2 Work

3 See also

4 Books by Mead

5 Writings about Mead

6 External links

(cited from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Herbert_Mead)

4. Mediation

Mediation, in a broad sense, consists of a cognitive process of reconciling mutually interdependent, opposed terms as what one could loosely call "an interpretation" or "an understanding of". The German philosopher Hegel uses the term 'dialectical unity' to designate such thought-processes. This article discusses the legal communications usage of the term. Other Wikipedia articles, such as Critical Theory, treat other usages or "senses" of the term mediation, as for example cultural and biological.

For the Wikipedia mediation process for resolving disputes, see Wikipedia:Mediation.

For statistical mediation, see Mediation (Statistics). For mediation in computer science, see Data mediation. For mediation in Marxist theory and media studies, see Mediation (Marxist theory and media studies).

Mediation, a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) or "appropriate dispute resolution", aims to assist two (or more) disputants in reaching an agreement. The parties themselves determine the conditions of any settlements reached— rather than accepting something imposed by a third party. The disputes may involve (as parties) states, organizations, communities, individuals or other representatives with a vested interest in the outcome.

Mediators use appropriate techniques and/or skills to open and/or improve dialogue between disputants, aiming to help the parties reach an agreement (with concrete effects) on the disputed matter. Normally, all parties must view the mediator as impartial.

Disputants may use mediation in a variety of disputes, such as commercial, legal, diplomatic, workplace, community and family matters.

A third-party representative may contract and mediate between (say) unions and corporations. When a workers’ union goes on strike, a dispute takes place, and the corporation hires a third party to intervene in attempt to settle a contract or agreement between the union and the corporation.

Contents

1 History of mediation

2 Mediation and conciliation

3 Why choose mediation

4 Mediation in the franchising sector

5 Early neutral evaluation and mediation

6 Mediator education and training

7 Mediator codes of conduct

8 Accreditation of ADR in Australia

9 Reference links

10 Uses of mediation

10.1 Native-title mediation in Australia

11 Philosophy of mediation

11.1 The uses of mediation in preventing conflicts

11.2 Responsibilities regarding confidentiality in mediation

11.3 Legal implications of mediated agreements

12 Common aspects of mediation

13 Online mediation

14 Mediation in business and in commerce

15 Mediation and litigation

16 Community mediation

17 Competence of the mediator

18 When to use mediation

18.1 Factors relating to the parties

19 Preparing for mediation

19.1 References for Preparing for Mediation in Australia

20 Mediation as a method of dispute resolution

20.1 Safety, fairness, closure

21 Post-mediation activities

21.1 Ratification and review

21.2 Official sanctions

21.3 Referrals and reporting-obligations

21.4 Mediator debriefing

22 Mediator roles and functions

22.1 Creating favorable conditions for the parties' decision-making

22.2 Assisting the parties to communicate

22.3 Facilitating the parties' negotiations

23 Functions of the parties

23.1 Preparation

23.2 Disclosure of information

23.3 Party participation

24 Choice of mediator

25 Values of mediation

25.1 Mediation with arbitration

26 Mediator liability

26.1 Mediators' liability in Tapoohi v Lewenberg (Australia)

26.2 Mediation in the United States

26.3 Without-prejudice privilege

27 Mediation in politics and in diplomacy

27.1 One of many non-violent methods of dispute resolution

28 Mediation and industrial relations

29 The workplace and mediation

30 Conflict-management

30.1 Measuring the effectiveness of conflict management

31 Confidentiality and mediation

32 Global relevance

32.1 Fairness

33 Bibliography

34 See also

35 Notes

36 External links

(Cited from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mediation)

5. Psychological Tools

The concept of "psychological tools" is a cornerstone of L. S. Vygotsky's sociocultural theory of cognitive development. Psychological tools are the symbolic cultural artifacts--signs, symbols, texts, formulae, and most fundamentally, language--that enable us to master psychological functions like memory, perception, and attention in ways appropriate to our cultures. In this lucid book, Alex Kozulin argues that the concept offers a useful way to analyze cross-cultural differences in thought and to develop practical strategies for educating immigrant children from widely different cultures.

Kozulin begins by offering an overview of Vygotsky's theory, which argues that consciousness arises from communication as civilization transforms "natural" psychological functions into "cultural" ones. He also compares sociocultural theory to other innovative approaches to learning, cognitive education in particular. And in a vivid case study, the author describes his work with recent Ethiopian immigrants to Israel, whose traditional modes of learning were oral and imitative, and who consequently proved to be quick at learning conversational Hebrew, but who struggled with the reading, writing, and formal problem solving required by a Western classroom. Last, Kozulin develops Vygotsky's concept of psychological tools to promote literature as a useful tool in cognitive development.

With its explication of Vygotsky's theory, its case study of sociocultural pedagogy, and its suggested use of literary text for cognitive development, "Psychological Tools will be of considerable interest to research psychologists and educators alike.

(Cited from: http://shopping.yahoo.com/p:Psychological%20Tools:%20A%20Sociocultural%20Approach%20to%20Education:3000389692)

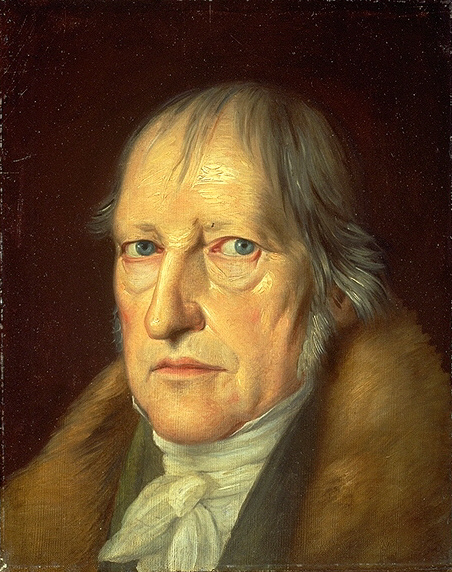

6. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

(August 27, 1770 – November 14, 1831) was a German philosopher, and with Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, one of the creators of German idealism.

(August 27, 1770 – November 14, 1831) was a German philosopher, and with Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, one of the creators of German idealism.Hegel influenced writers of widely varying positions, including both his admirers (Bauer, Feuerbach, Marx, Bradley, Dewey, Sartre, Küng, Kojève, Žižek), and his detractors (Schelling, Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Peirce, Russell). Hegel developed a comprehensive philosophical framework, or "system", to account in an integrated and developmental way for the relation of mind and nature, the subject and object of knowledge, and psychology, the state, history, art, religion, and philosophy. In particular, he developed a concept of mind or spirit that manifested itself in a set of contradictions and oppositions that it ultimately integrated and united, such as those between nature and freedom, and immanence and transcendence, without eliminating either pole or reducing it to the other. His influential conceptions are of speculative logic or "dialectic," "absolute idealism," "Spirit," negativity, sublation (Aufhebung in German), the "Master/Slave" dialectic, "ethical life," and the importance of history.

Contents

1 Life

1.1 Early years: 1770-1807

1.1.1 Childhood in Stuttgart

1.2 Student in Tübingen (1788-93)

1.2.1 House tutor in Berne (1793-96) and Frankfurt (1797-1801)

1.3 Jena, Bamberg and Nuremberg: 1801-1816

1.3.1 Early university career in Jena (1801-1807)

1.3.2 Newspaper editor in Bamberg (1807-08) and headmaster in Nuremberg (1808-15)

1.4 Professor in Heidelberg and Berlin: 1816-1831

1.4.1 Heidelberg (1816-18)

1.4.2 Berlin (1818-31)

2 Works

3 His thought

3.1 The concept of freedom through Hegel's method

3.2 Progress through contradictions and negations

3.3 Civil society

3.4 Hegel and Heraclitus

3.5 Influence

4 Hegel's legacy (interpretation)

4.1 Reading Hegel

4.2 Left and Right Hegelianism

4.3 Triads

5 Advocates

6 Detractors

6.1 Obscurantism

6.2 The Absolute

6.3 Totalitarianism

6.4 Natural Sciences

6.5 Psychology

7 Works

7.1 Published during Hegel's lifetime

7.2 Published posthumously

8 Secondary literature

8.1 General introductions

8.2 Essays

8.3 Biography

8.4 Historical

8.5 Hegel's development

8.6 Recent English-language literature

8.7 Phenomenology of Spirit

8.8 Logic

8.9 Politics

8.10 Religion

8.11 Hegel's reputation

9 Volume numbers and divisions, translations

10 Notes

11 See also

12 External links

12.1 Hegel's texts online

(Cited from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hegelian)

7. Sensor and motor

Sensory-motor skills are an important category of learning in many tasks and occupations (not to mention all forms of sports). Motor skills can be classified as continuous (e.g. tracking), discrete, or procedural movements. The last category of skills are probably most relevant to real world applications such as typing, operating instruments, or maintenance.

Behavioral psychology (e.g., Guthrie, Hull, Skinner) emphasized practice variables in sensory-motor skills such as massed versus spaced practice, part versus whole task learning, and feedback/reinforcement schedules. Long-term retention of motor skills depends upon regular practice; however, continuous responses show less forgetting in the absence of practice than discrete or procedural skills. Repetition after task proficiency is achieved (overtraining) and refresher training reduce the effects of forgetting. Unlike verbal learning, sensory-motor learning appears to be the same under massed and spaced practice. Learning and retention of sensory-motor skills is improved by both the quantity and quality of feedback (knowledge of results) during training.

Marteniuk (1976) presents a theoretical framework for sensory-motor skills based upon information processing theory. This framework emphasizes the importance of feedback in correcting motor behavior and selective attention in determining what actions are taken. Marteniuk suggests two ways in which learning/teaching of motor skills can be facilitated: (1) slow down the rate at which information is presented, and (2) reducing the amount of information that needs to processed.

Singer (1975) examined the importance of prompting and guidance while learning motor skills relative to trial and error or discovery strategies. His research suggests that some form of guided learning seems most appropriate when high proficiency on a new skill is involved. On the other hand, if the task is to be recalled and transferred to a new situation, then some type of problem-solving strategy may be better. In addition, guided learning may be most effective in early training while trail and error is important in advanced training. Singer suggests that the choice of instructional strategy for motor skills should depend upon the purpose and nature of the task.

Card, Moran & Newell outlined a model called GOMS (Goal-Operation-Method-Selection) which accounts for the sensory-motor and cognitive aspects of computer input tasks.

There is evidence that mental rehearsal, especially involving imagery, facilitates performance. This may be because it allows additional memory processing related to physical tasks (e.g., the formation of schema ) or because it maintains arousal or motivation for an activity.

Many forms of sensory-motor behavior are learned by imitation, especially complex movements such as dance, signing, crafts, or surgery. Consequently, theories of social learning and development (e.g. Bandura, Vygotsky) are relevant to sensory-motor activities.

Finally, theories of individual differences, such as Guilford or Gardner, have identified a broad range of sensory-motor abilities that vary across individuals.

References:

Adams, J.A. (1987). Historical review and appraisal of research on the learning, retention, and transfer of human motor skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 41-74.

Singer, R.N. (1975). Motor Learning and Human Performance (2nd Ed.). New York: Macmillan.

Marteniuk, R. (1976). Information Processing in Motor Skills. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

(Cited from:http://tip.psychology.org/sensory.html)

8. Semiotics

Semiotics, also called semiotic studies or semiology, is the study of sign processes (semiosis), or signification and communication, signs and symbols, both individually and grouped into sign systems. It includes the study of how meaning is constructed and understood.

One of the attempts to formalize the field was most notably led by the Vienna Circle and presented in their International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, in which the authors agreed on breaking out the field, which they called "semiotic", into three branches:

Semantics: Relation between signs and the things they refer to, their denotata.

Syntactics: Relation of signs to each other in formal structures.

Pragmatics: Relation of signs to their impacts on those who use them. (Also known as General Semantics)

These branches are clearly inspired by Charles W. Morris, especially his Writings on the general theory of signs (The Hague, The Netherlands, Mouton, 1971, orig. 1938).

Semiotics is frequently seen as having important anthropological dimensions, for example Umberto Eco proposes that every cultural phenomenon can be studied as communication. However, some semioticians focus on the logical dimensions of the science. They examine areas belonging also to the natural sciences - such as how organisms make predictions about, and adapt to, their semiotic niche in the world (see semiosis). In general, semiotic theories take signs or sign systems as their object of study: the communication of information in living organisms is covered in biosemiotics or zoosemiosis.

Syntactics is the branch of semiotics that deals with the formal properties of signs and symbols.[1] More precisely, syntactics deals with the "rules that govern how words are combined to form phrases and sentences."[2]. Charles Morris adds that semantics deals with the relation of signs to their designata and the objects which they may or do denote; and, pragmatics deals with the biotic aspects of semiosis, that is, with all the psychological, biological, and sociological phenomena which occur in the functioning of signs.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 Formulations

3 History

4 Some important semioticians

5 Current applications

6 Branches

7 Pictoral Semiotics

8 Semiotics food

9 See also

10 Bibliography

11 References

12 Further reading

13 Footnotes

(Cited from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semiotic)

9. Mnemonic

A mnemonic device (pronounced "neh-mon-ik") is a memory and/or learning aid. Commonly met mnemonics are often verbal, something such as a very short poem or a special word used to help a person remember something, particularly lists, but may be visual, kinesthetic or auditory. Mnemonics rely on associations between easy-to-remember constructs which can be related back to the data that is to be remembered. This is based on the principle that the human mind much more easily remembers spatial, personal, surprising, sexual or humorous or otherwise meaningful information than arbitrary sequences.

The word mnemonic is derived from the Ancient Greek word μνημονικός mnemonikos ("of memory") and is related to Mnemosyne ("remembrance"), the name of the goddess of memory in Greek mythology. Both of these words refer back to μνημα mnema ("remembrance").[1] Mnemonics in antiquity were most often considered in the context of what is today known as the Art of Memory.

The major assumption in antiquity was that there are two sorts of memory: the "natural" memory and the "artificial" memory. The former is inborn, and is the one that everyone uses every day. The artificial memory is one that is trained through learning and practicing a variety of mnemonic techniques. The latter can be used to perform feats of memory that are quite extraordinary, impossible to carry out using the natural memory alone.

Contents

1 First letter mnemonics

2 Other mnemonic systems

3 Arbitrariness of mnemonics

4 Assembly mnemonics

5 Mnemonics in foreign language acquisition

6 History of mnemonics

7 References

8 External links

(Cited from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mnemonic)

10. Superseded scientific theories

A superseded, or obsolete, scientific theory is a scientific theory that was once commonly accepted, but that is no longer considered the most complete description of reality by a mainstream scientific consensus; or a falsifiable theory which has been shown to be false. This label does not cover protoscientific or fringe science theories with limited support in the scientific community, nor does it describe theories that were never widely accepted. Some theories which were only supported under specific political authorities, like Lysenkoism, may also be described as obsolete or superseded.

In some cases, a theory or idea is found to be baseless and is simply discarded: for example, the phlogiston theory was entirely replaced by the quite different concept of energy and related laws. In other cases, an existing theory is replaced by a new theory which retains elements of the earlier theory; in these cases, the older theory is often still useful because it provides a description that is "good enough" for many purposes, is more easily understood than the complete theory, and may lead to simpler calculations. An example of this is the use of Newtonian physics, which differs from the currently accepted relativistic physics by a factor which is negligibly small at velocities much lower than that of light. Newtonian physics is so satisfactory for most purposes that many secondary educational systems teach it, but not the "correct" relativity. Another case is the theory that the earth is approximately flat; while clearly wrong for long distances, viewing a landscape as flat it is still sufficient for most local maps and surveying.

Karl Popper suggested that a theory should be considered scientific if and only if it can in principle be falsified by experiment; any idea not susceptible to falsification does not belong to science.

Contents

1 Superseded biology theories

2 Superseded chemistry theories

3 Superseded physics theories

4 Superseded astronomical and cosmological theories

5 Superseded geographical and climatological theories

6 Superseded geological theories

7 Superseded psychological theories

8 Superseded medical theories

9 Obsolete branches of enquiry

10 Theories now considered to be approximations

11 See also

11.1 Lists

(Cited from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superseded_scientific_theories)